Setting: The cloister of a convent near Siena.

Because of the scandal caused by her having an illegitimate child, Sister Angelica has done penance in a convent for seven years. The Princess, Sister Angelica’s aunt, arrives unexpectedly and demands that Sister Angelica sign a document renouncing her right to any inheritance and turning it over to her sister who is about to be married. The Princess refuses to forgive Sister Angelica, who inquires about the fate of her son. The Princess coldly tells her that the child has been dead for two years. Devastated by the news and the coldness of her aunt, Sister Angelica takes poison. She then realizes, too late, that she has committed a mortal sin and asks the Virgin Mary to forgive her and give her a sign her prayer has been answered.

by Kaitlyn Canneto

Trouble in Tahiti (1952) opens with a Greek trio chorus, illustrating the conventions of a day in the life of a suburban marriage in the 1950s. Inside, husband and wife Sam and Dinah are in the middle of a daily argument that they cannot escape—the fight to be kind to each other. While Sam is on his way out of the house to work, Dinah reminds him that their son, Junior’s, play is that evening. Much to Dinah’s chagrin, Sam excuses himself from attending the play due to the handball tournament at his gym. While Sam is happily at work, Dinah details a nightmare to her psychiatrist, in which she is trapped in a dead garden without an escape in sight. In her dream, a voice tells her about another garden that is prosperous—unlike the one she is tangled in—which she longs for, in a way that parallels her marriage. Midday, Sam and Dinah run into one another on the street and discuss the prospect of meeting for lunch, yet they lie to each other to avoid time together. Later, at the gym, Sam reveals his priority to succeed as a man above all else. At the cinema, Dinah sees Trouble in Tahiti, and she finds herself lustful for the exotic “island magic” that is described on the silver screen. The two meet at home, where they attempt to discuss their marriage, which only ends in another argument. They discover that neither of them went to Junior’s play. Instead of trying to resolve their differences, they instead go to the cinema to buy another escape to temporary happiness.

by Kaitlyn Canneto

Ph.D. Musicology Student

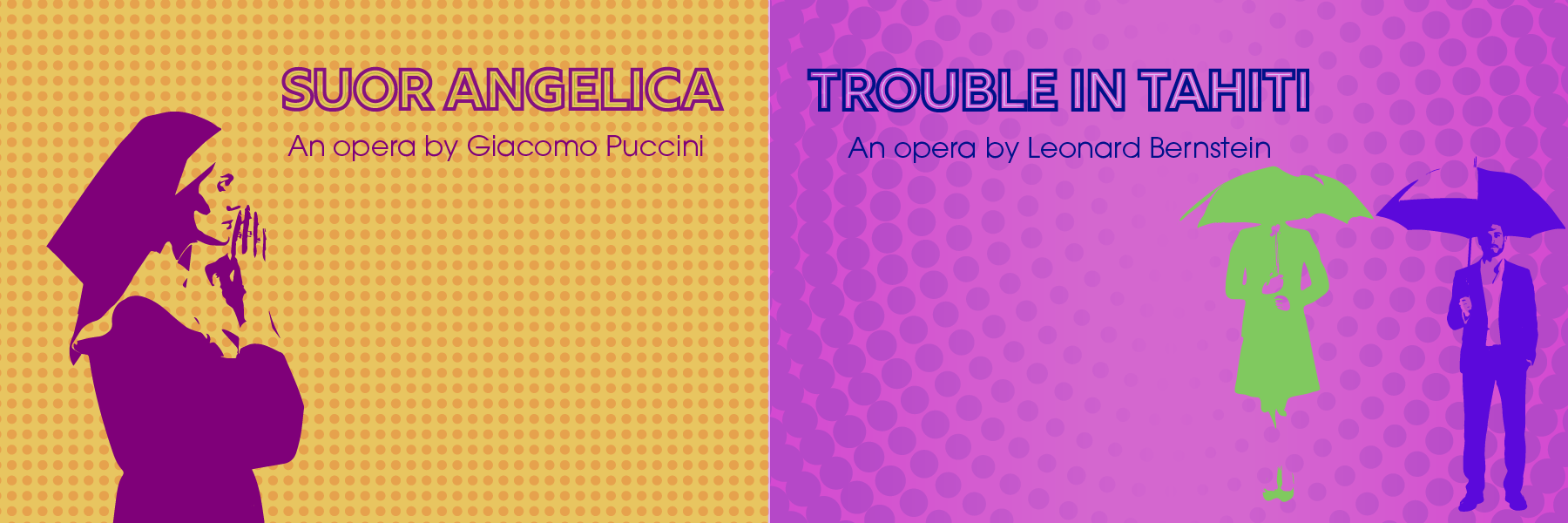

Suor Angelica (Sister Angelica) premiered on December 14, 1918, at the Metropolitan Opera in a series of three one-act operas collectively titled Il trittico (The Triptych), composed by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924). These were the final operatic works completed by Puccini before his death six years later. Puccini sought to create shorter operatic works toward the end of his career in contrast with his earlier grand operas such as La Bohème (1896) and Madama Butterfly (1904). While Puccini was developing the one-act works that would become the Trittico, Italian playwright Giovacchino Forzano approached the composer with a drama about a nun, and Puccini delightedly accepted. Set in a seventeenth-century Italian convent and performed by an all-female cast, Suor Angelica provides a contrast against the first and third parts of the Trittico. The first opera, Il tabarro (The Cloak), is set in Paris in 1910, and the third opera, Gianni Schicchi, takes place in Florence in 1299. Although Puccini initially instructed that Il trittico be staged in its entirety, by 1920, the Royal Opera House, London, set the precedent of staging the operas separately. To date, Suor Angelica is the least performed of the three operas, overlooking the nuance and significance of Puccini and Forzano’s original work.

Suor Angelica is dubbed an opera seria for its tragic ending, yet Forzano’s libretto is driven by irony and humor. Forzano introduces the audience to the convent with a focus on the titular nun, Angelica, who is only a nun by consequence of sin and has left behind an upper-class life. Throughout the opera, Forzano provides the audience with comedic scenes between the nuns, unexpected in a serious work.

The opera opens with nuns in a chapel singing the Ave Maria. After this demonstration of faith and purity, the following scene introduces the audience to the reality that nuns sin, too. Here, the monitor nun orders penance to the sinning sisters, including Sister Osmina for theft of roses from the garden, to which Osmina demands her innocence. In some productions, rose pedals subsequently fall from Osmina’s sleeves, breaking from the seriousness of the scene. Further, in the following scene, the sisters discuss their desires; Sister Dolcina chimes in to declare her wish, accompanied by a playful motive, to which her fellow sisters sarcastically beat her to the punch. They collectively state, “La gola è colpa grave! È golosa! (Greed is a serious sin! She’s greedy!),” as though the garden were a schoolyard, and the nuns were mocking their classmate. This motive reappears in the following scene when the alms-collectors deliver goods to the convent, to which Sister Dolcina excitedly reacts “unable to control herself,” as marked in the libretto. The continued humor throughout Suor Angelica provides a depth of entertainment to the opera and a relief to the tragic (yet moving) ending.

Set in “any American city, and its suburbs,” according to composer and librettist Leonard Bernstein, Trouble in Tahiti demonstrates irony less subtly than Puccini’s Suor Angelica, while exposing realities behind the idealized American nuclear family. This one-act opera premiered on June 23, 1952, at Brandeis University’s inaugural Festival of the Creative Arts, directed by Bernstein himself. Then, Bernstein was a visiting music professor at the Boston-area institution and still early in his career composing for the stage. Trouble in Tahiti—a play on the idiom “trouble in paradise”—follows a marriage at stalemate, where husband and wife Sam and Dinah, respectively, each long for love but fail to communicate with each other and instead masquerade behind their white picket fence. The focus on marriage reflects developments in Bernstein’s own life, as he began his first operatic work around the time of his honeymoon and continued to write both the music and text during the honeymoon.

The opera consists of seven scenes that occur within a day to capture the dynamic of Sam and Dinah’s marriage and their individual perspectives. A Trio (soprano, tenor, baritone) opens the opera in a prelude, acting as a narrator for the happy marriage-masquerade Sam and Dinah hide behind. Throughout the scenes, the trio reappears as the internal dialogue of Sam, characters in the film Trouble in Tahiti that Dinah sees, and again as a narrator to further the plot. Given the minimal cast, the only dialogue in the opera occurs between the unhappily married couple, and these moments only happen in three of the seven scenes, where the two argue with each other. Otherwise, the audiences learn from Sam’s and Dinah’s arias and solos that Sam prioritizes himself over his wife and family, and Dinah experiences a haunting dream in which she ultimately escapes to a garden she details to her therapist, akin to the escape of “Island Magic” she later sees at the movie theater.

The opera underscores the universality of Sam and Dinah’s marital dynamics. The Trio’s opening prelude involves a cadential motive with the text “the little white house in . . .” followed by the name of a different U.S. suburb (e.g., Scarsdale, Wellesley Hills, Elkins Park) with each repetition. In doing so, Bernstein implies that a marriage like Sam and Dinah’s can materialize anywhere. Further, in the score, the composer-librettist explicitly calls for minimal set pieces and, instead, the use of lighting and backdrops to create scenery that strips the scene of a specific location or period and clarifies the ubiquity of domestic distress.

Throughout the opera, it becomes clear from their arguments and laments that Sam and Dinah desire a happier marriage, which they once had. Bernstein emphasizes this through contrasting motives. Bernstein scholar Helen Smith (2011) points out that, in Scene 1, Sam expresses anger and aggression with a D–A–D–C motive pattern, which Smith dubs the “conflict motive.” The inconsistent contour against Bernstein’s quartal chords reflects the tension between the married couple. Further, Smith points to continued sonic tension with an inversion of this motive in Dinah’s solo about her dream in Scene 3.

The opera concludes with Sam and Dinah avoiding an actual conversation about their relationship, instead, escaping, once again, to the movies and leaving their problems unresolved. In 1980, Bernstein and writer Stephen Wadsworth created a full-length operatic sequel to the one-act, titled A Quiet Place (1983). This work, which takes place 30 years after Trouble in Tahiti, follows the same family, as Sam and his children cope with the sudden death of Dinah. After multiple revisions, the sequel opera would interpolate Trouble in Tahiti.

This production provides a unique pairing of two contrasting works—from a seventeenth-century Italian nun to a twentieth-century American couple, each navigating their own unfortunate circumstances with humor, tragedy, and irony.